Epiphany (or Theophany, if you’re in the East) isn’t commemorating the arrival of the magi at Bethlehem. They weren’t that big a deal; we don’t even know their names.

No, “epiphany” means “revelation from above;” “theophany” means “revelation of God.” On Christmas, we celebrate the Incarnation of God, God becoming human (in- and caro, meaning "to make into flesh"). What we’re celebrating today is the revelation of the incarnation, i.e. the point when (some) people started to figure out that the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us.1 Obviously, the Incarnation is important, but it doesn’t help us much if we don’t know about it.

So let’s play “We Three Kings” one more time and find out.

Reading I

Is 60:1-6

Rise up in splendor, Jerusalem! Your light has come, the glory of the Lord shines upon you. See, darkness covers the earth, and thick clouds cover the peoples; but upon you the LORD shines, and over you appears his glory. Nations shall walk by your light, and kings by your shining radiance. Raise your eyes and look about; they all gather and come to you: your sons come from afar, and your daughters in the arms of their nurses.

Then you shall be radiant at what you see, your heart shall throb and overflow, for the riches of the sea shall be emptied out before you, the wealth of nations shall be brought to you. Caravans of camels shall fill you, dromedaries from Midian and Ephah; all from Sheba shall come bearing gold and frankincense, and proclaiming the praises of the LORD.

In Matthew, as we’ll see in a moment, Jesus visitors were Magi from the east. Matthew doesn’t say anything about kings, so why are we always singing “We Three Kings?”

One reason is this passage from Isaiah. As we saw during Advent, Isaiah prophesized about the messiah quite a bit. It’s not difficult to tie this to Jesus (“Your light has come”), so it makes sense that the kings referred to must be the magi.

While “magi” can reasonably be translated as “wise men,” “professors,” or “scholars,” it wasn’t unusual for magi to be kings, or vice versa. Solomon wasn’t the only wise king, after all. The king of Babylon set Daniel above his magi after he interpreted the king’s dreams.2

But whatever you call them, I think the magi’s official title is less important than where they come from. Entire “nations shall walk by your light,” including Midian, Ephah, and Sheba. It’s a way of saying “basically everyone,” not just Israel.

Which is why it’s interesting that some early Christians thought everyone should have to convert to Judaism before becoming Christians. The debate was settled in the First Council of Jerusalem,3 and I wouldn't be surprised if Isaiah was cited in their debate.

Catholicism is the universal church. No matter what nation you’re from, you’re invited to worship the newborn king.

Responsorial Psalm

Ps 72:1-2, 7-8, 10-11, 12-13.

R. Lord, every nation on earth will adore you.

O God, with your judgment endow the king,

and with your justice, the king’s son;

He shall govern your people with justice

and your afflicted ones with judgment.

R. Lord, every nation on earth will adore you.

Justice shall flower in his days,

and profound peace, till the moon be no more.

May he rule from sea to sea,

and from the River to the ends of the earth.

R. Lord, every nation on earth will adore you.

The kings of Tarshish and the Isles shall offer gifts;

the kings of Arabia and Seba shall bring tribute.

All kings shall pay him homage,

all nations shall serve him.

R. Lord, every nation on earth will adore you.

For he shall rescue the poor when he cries out,

and the afflicted when he has no one to help him.

He shall have pity for the lowly and the poor;

the lives of the poor he shall save.

R. Lord, every nation on earth will adore you.

John Calvin, the 16th century apostate, refused to believe the magi were three kings: “But the most ridiculous contrivance of the Papists on this subject is, that those men were kings. Beyond all doubt, they have been stupefied by a righteous judgment of God, that all might laugh at [their] gross ignorance.”

On the other hand, Tertullian, a second century scholar, considered the Magi to be kings. So, you know, this wasn’t new even when Calvin wrote about it 500 years ago.4

Tertullian argued their visit fulfilled Solomon’s prayer in Psalm 72: “The kings of Tarshish and the Isles shall offer gifts; the kings of Arabia and Seba shall bring tribute.” Again, this obviously sounds a lot like the Magi.

But just like with Isaiah, more relevant to us is: “All kings shall pay him homage, all nations shall serve him.” I’ve never been to Israel (or Seba or Tarshish), but the Psalmist is still inviting everyone to pay homage. And we do, every week at mass.

Reading II

Eph 3:2-3a, 5-6

Brothers and sisters: You have heard of the stewardship of God’s grace that was given to me for your benefit, namely, that the mystery was made known to me by revelation. It was not made known to people in other generations as it has now been revealed to his holy apostles and prophets by the Spirit: that the Gentiles are coheirs, members of the same body, and copartners in the promise in Christ Jesus through the gospel.

Paul’s letter to the Ephesians is less to the Ephesians specifically and more to the Universal Church as a whole. Ephesus is in the far east, so Paul takes the opportunity to explain that the Gospel is for everyone.

He places them in the great continuity of revelation, from the Chosen People and their prophets to Jesus, who revealed himself to the apostles, and then sent them to the far corners of the world to spread the Good News. As the apostles pass away (usually horribly), it falls on their heirs to continue their work.

Paul wants the Gentiles to know that we are coheirs, members of the same body of the Church. We’re much farther away from Paul than the Ephesians, but he’s still writing to us with the same marching orders.

Alleluia

Mt 2:2

R. Alleluia, alleluia.

We saw his star at its rising

and have come to do him homage.

R. Alleluia, alleluia.

There’s a trend in modern interpretations of Bible stories to try and find “natural” explanations to miracles. For example, people try to attribute the Feeding of the Multitudes to the Miracle of Sharing™. Which is a completely atextual reading of the story, since Jesus refers to these events later on when talking about the Pharisees and Sadducees.5

And what about the star the Magi follow? That’s gotta be a miracle, right?

Matthew doesn’t actually say it’s a miracle anywhere; he doesn’t attribute the star’s appearance to God’s command. And if the star is doing the prophesying on its own, well, that’d be astrology. Matthew, the evangalist writing to the Jews of his time, probably wouldn’t find that Kosher.6

There are actually a few theories of how a star could suddenly “appear,” and then “lead” the Magi, but here’s the one I find most convincing:

When Matthew says the star “preceded them” or “went before them” (depending on your translation of proagō), it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s moving like a modern satellite. In fact, that wouldn’t even make sense from a visual perspective. At the speed of horse or camelback, a star isn’t really going to look like it’s moving, anyway.

Have you ever looked out the window of your car at night, and seen the moon “following” you? That’s because of an optical effect called parallax. The same would be true of a bright star.

What about the second part of the statement, “it came to rest over the place where the child was”? The Greek verb for “to rest,” histēmi, can simply mean “to stand there,” which fits with the Magi seeing, from their perspective, the star in the sky over the place where the child was as they approached.

But were they following a “star,” in our modern understanding? Maybe not. Astronomers at the time didn’t distinguish between what we now know are planets and stars; they just knew that those moved differently. But the magi say that the star “appeared.” Planet or star, there haven’t been any new ones in a long, long time.

Except…

Around 3 B.C.,7 the star Regulus lined up with Jupiter and Venus for a time, which would look to ancient people like a "new," brighter "star." The Babylonians had a prophesy that “If Jupiter passes Regulus and gets ahead of it, and afterwards, Regulus, which it had passed and got ahead of it, stays within its setting, someone will rise and kill the king and seize the throne.” Which thus explains magi from the east coming to Israel, looking for a new king?

So, why would I prefer this explanation to, say, God simply creating a new star and moving it around for the wise men? Mostly because somebody else would’ve noticed it.

Contrary to popular belief, a lot of stories about Jesus and his miracles were recorded in (near) contemporaneous histories, not just the Gospels. These other accounts were skeptical, sure, but at least people seemed to be aware of a miracle worker in some backwater corner of the Roman Empire.

If a star had been floating around Israel, Egyptians, Romans, and who knows what other astronomers from far-flung places would have seen and noted it. There are no such records, that I’m aware of.

They did note the alignment of the planets, but lacking the Babylonian prophesy, didn’t interpret it as the arrival of a new king.

Is it a miracle that this prophesy existed to coincide with Jesus’ birth? Probably. God has plans that go on for millennia. He could have moved the stars for His only Son, but in this case, I just don’t think so.

Gospel

Mt 2:1-12

When Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea, in the days of King Herod, behold, magi from the east arrived in Jerusalem, saying, “Where is the newborn king of the Jews? We saw his star at its rising and have come to do him homage.”

When King Herod heard this, he was greatly troubled, and all Jerusalem with him. Assembling all the chief priests and the scribes of the people, He inquired of them where the Christ was to be born. They said to him, “In Bethlehem of Judea, for thus it has been written through the prophet: And you, Bethlehem, land of Judah, are by no means least among the rulers of Judah; since from you shall come a ruler, who is to shepherd my people Israel.”

Then Herod called the magi secretly and ascertained from them the time of the star’s appearance. He sent them to Bethlehem and said, “Go and search diligently for the child. When you have found him, bring me word, that I too may go and do him homage.”

After their audience with the king they set out. And behold, the star that they had seen at its rising preceded them, until it came and stopped over the place where the child was. They were overjoyed at seeing the star, and on entering the house they saw the child with Mary his mother. They prostrated themselves and did him homage. Then they opened their treasures and offered him gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. And having been warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they departed for their country by another way.

Okay, one more bit of trivia: we don’t actually know if there were three kings/magi/wise men. We know they brought three types of gifts, but there could’ve been 6, 9, or 12 of them, or maybe a prime number, and they just pooled their money together to buy three gifts as a group.

It’s worth contrasting these wise guys with the shepherds in Luke’s story.8 The shepherds, who were not educated, wouldn't have noticed the alignment of Jupiter and Venus. But they certainly did notice angels sweetly singing o’er the plains. God sent His messengers first to these poor, dirty, lonely men. They were the first ones to encounter Christ, besides Joseph and Mary.

The three kings, following their own pagan prophesy, thought it made sense to go to the nearest earthly king, Herod. (Who wasn’t a good guy, you may remember.) Herod consults with his own wise men (because he apparently didn’t bother to study his own holy books, unlike the magi), and tells these foreigners to go to a grubby little town of no Earthly significance.

When they arrived, I’m sure they were shocked to see the Holy Family in a stable, surrounded by animals. But they still prostrated themselves and offered their gifts. Because it doesn’t matter how or where you encounter God, when you do, it’s time to pay tribute and sing his praises.

Now, the next part of the story is a miracle. They were warned in a dream to not tell Herod what they found, and go home on a different route. I imagine Herod must’ve been pretty pissed off. He thought he was dealing with peers, but instead, they sneak off home, leaving him with some child king running around somewhere down south in Bethlehem. His anger unfortunately leads directly to the Massacre of the Infants.

Life can go back and forth like this, with tragedies following miracles, following tragedies again, and on and on. The story doesn’t really end. Even when Jesus died, it’s not over.

And thanks to Him, death is no longer the end for us, either. That’s what was revealed centuries ago, and still today.

Further Reading

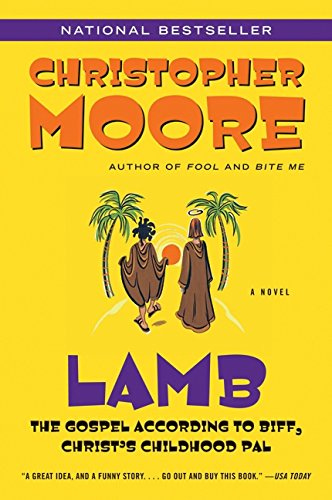

The story of the magi reminds me of one of my favorite books, Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal, by Christopher Moore.

Now, I know how that title sounds. But while the book is goofy and a bit silly, it is not irreverent or irreligious. In fact, it seems Moore made a special effort not to contradict anything in the canonical Gospels.

This is the story of the time between the Finding in the Temple and Baptism of the Lord, the so-called “silent years.” It’s not in any way meant to be an earnest history or biography; as I said, it’s a funny book. But it is an honest and imaginative look at how Jesus may have reacted to his own calling.

The reason I bring it up today is that the main part of the story, the 2nd act, in dramatic terms, is Jesus tracking down the three magi, Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar, to find out what they were looking for, exactly. Each one is used to represent a different eastern religion or faith system, and also acts in a Shakespeare in Love-type origin for many of Jesus’ parables.

It’s very light reading, and I laughed out loud at many parts, but the theme and theological implications are surprisingly deep. I highly recommend picking up a copy.

Fun fact: Calvin the comic strip character is, in fact, named after John Calvin the, er, “theologian.”

Remember, Dionysius Exiguus didn’t calculate Jesus’ birth exactly right.